An overview of the exciting initiative bringing together local leaders in the Georgian Bay Biosphere region.

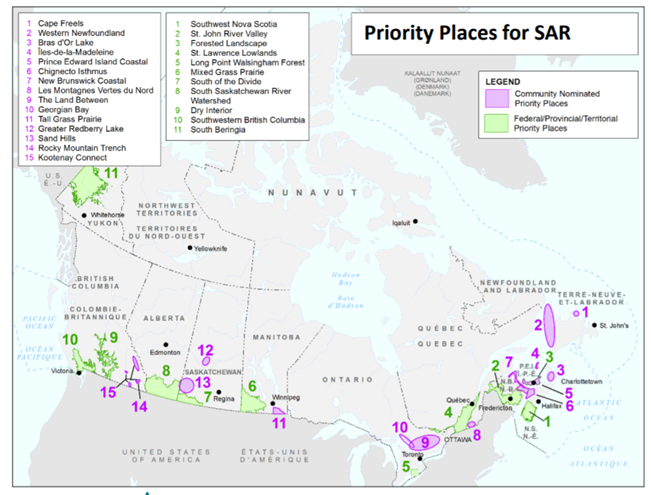

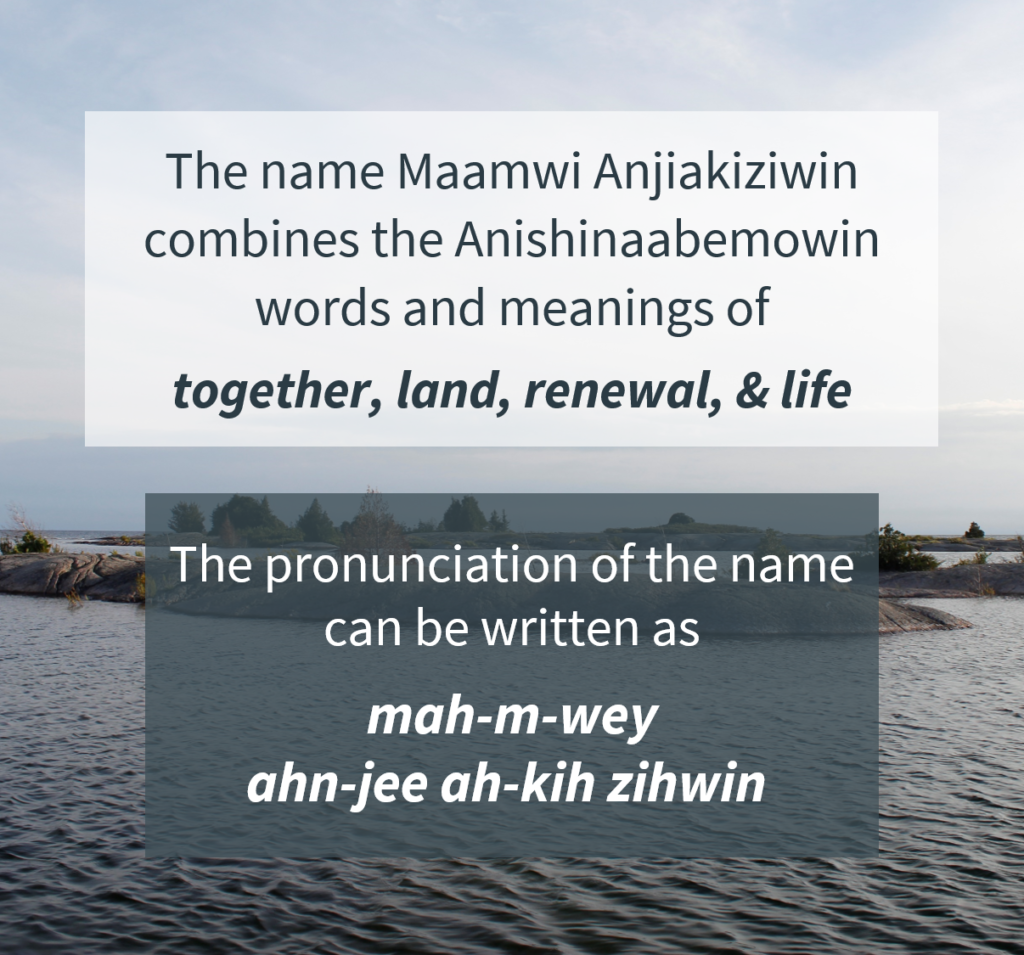

The Maamwi Anjiakiziwin initiative is a collaboration of local leaders in ecological, cultural, and planning work along eastern Georgian Bay. Maamwi Anjiakiziwin is part of a larger Canada-wide program called Community Nominated Priority Places (CNPP). The CNPP program is administered by Environment and Climate Change Canada through its Canada Nature Fund, which supports partnerships in protecting and recovering species at risk in Canada. Rather than focusing efforts on a single species, CNPP aims to conserve multiple species and entire ecosystems. Funding is provided for four years (beginning in 2019); however, the intention is to develop long-term strategies to sustain CNPP collaborations into the future. This federal program currently supports 15 CNPP projects across Canada, one of which is Maamwi Anjiakiziwin here in the UNESCO Georgian Bay Biosphere region.

The multi-species conservation approach is no small task, and to be successful the Maamwi Anjiakiziwin initiative relies on the power of collaboration. This partnership includes communities, organizations, municipalities, and individuals – many of whom have been researching species at risk on the Georgian Bay coast for years before this initiative began. The goal is that the relationships, understanding, and approaches developed through this initiative will be carried on for generations to come.

This introduction to Maamwi Anjiakiziwin will explain our collaborative approach and highlight some of our main priorities for conservation on eastern Georgian Bay.

Bringing People Together for Conservation

Sharing knowledge and working together are integral to the success of Maamwi Anjiakiziwin. Right from the start, collaboration was needed to complete the application to become a federally-recognized Community Nominated Priority Place. Multiple organizations, communities, species experts, and individuals helped shape the application. The organizations used their financial and human resources as matching contributions to grant, while local municipalities and First Nations offered financial and service-based contributions.

Even now that the project is well underway, Maamwi Anjiakiziwin continues to rely on sharing and working together. It is important that all partners share their experience and knowledge, especially considering that some groups have traditionally been excluded from the decision-making process in environmental management and conservation. Cultural training for non-Indigenous partners about Anishinaabek knowledge systems has been especially important to raise awareness. Bringing everyone into the circle together with the goal of sharing, listening, and learning has strengthened our relationships with each other and with the land.

Guidance Using Two-Eyed Seeing

An approach known as ‘Two-Eyed Seeing’ guides decision-making in the Maamwi Anjiakiziwin initiative. Two-Eyed Seeing, as defined by Mi’kmaw Elder Albert Marshall, is the ability “to see from one eye with the strengths of Indigenous ways of knowing, and to see from the other eye with the strengths of Western ways of knowing, and to use both of these eyes together.” Using both of these ways of doing and knowing builds our understanding of our roles in the landscape and as caretakers of the land. For example, Maamwi Anjiakiziwin includes language and knowledge sharing; ceremonies for the care and release of turtle hatchlings into the wild; and asemma (tobacco) offerings during fieldwork. The role of the Mawaanji’iwe (getting people together) Manager provides learning opportunities and helps navigate the process of building relationships. More information on Treaties, protocols, the Seven Grandfather Teachings, and Anishinaabemowin (the Ojibwe language) is available on the Cultural Learning & Consultation page of our website.

An Adaptive Approach

Bringing people together and using Two-Eyed Seeing allows project partners to share information and values that help set and define priorities for conservation on eastern Georgian Bay. When everyone gets together, there are opportunities to have conversations, share observations, ask questions, create maps, and plan fieldwork programs. In the end, we share an understanding of what the priority conservation work will be, where it will occur, how it will be carried out, and how its effectiveness will be measured. When we use Two-Eyed Seeing in this process, we become better connected to the work and to each other; and we are motivated to carry out our work in a responsible way.

Most decisions regarding the Maamwi Anjiakiziwin initiative are made by the Steering Committee, comprised of members from: the Georgian Bay Biosphere (GBB), Georgian Bay Land Trust (GBLT), Magnetawan First Nation, Shawanaga First Nation, and Wasauksing First Nation. There are also other partners whose support makes the initiative possible. All throughout a project, the partners will get together to share perspectives. This style of project governance is adaptive, with opportunities to modify our work as we learn from each other. It allows us to make changes to improve the project before it is complete.

Back (L to R): Samantha Noganosh (Magnetawan First Nation); Greg Mason and David Bywater (GBB); Bill Lougheed (Georgian Bay Land Trust); Midwewekamigokwe (Sherrill) Judge (GBB).

Front (L to R): Tianna Burke (GBB); Alanna Smolarz (Magnetawan First Nation); Steven Kell (Shawanaga First Nation).

Photo credit: Tianna Burke.

Priorities for Conservation on Eastern Georgian Bay

Maamwi Anjiakiziwin has several key objectives to achieve through inter-related activities. These main activities are summarized below.

1. Reptile Road Ecology

We seek to understand threats faced by reptiles on local roads, identify areas where mortality would be improved by mitigation, and monitor the effects of mitigation on reptiles The information gathered through the program is used to inform Best Management Practices (BMPs) for road development and management in and around the Biosphere region.

2. Best Management Practices

We are developing strategies and approaches that better serve species at risk and can be easily incorporated into the activities of land use planners, lands managers, construction companies, and public works departments. So far, these have included species at risk training for construction teams, turtle nest excavation at construction sites, and incorporation of reptile mitigation in road improvements.

3. Land Use Planning

By improving the planning approaches and policies related to development and land use changes, the needs of species at risk are incorporated into land use planning decisions. A key component is mapping critical habitat for species at risk.

4. Community Science

The project uses the tool of iNaturalist to gather observations of nature from the public. iNaturalist is a free app for mobile devices that identifies species of flora and fauna by the photos submitted by users. Community members can submit species observations to help researchers learn about the distribution, range, and threats facing species in the Biosphere. Observations submitted to the Biosphere’s iNaturalist project are used to develop future monitoring programs and access needs for monitoring and research across the Biosphere.

5. Motus Towers

Installing Motus towers will provide opportunities to study and track wildlife through radio telemetry. This tool for monitoring flying species (such as birds and bats) will improve our understanding of how these species use the Biosphere at a landscape level. Learn more about this global network at motus.org.

These examples represent only some components of this exciting initiative. Drawing on the knowledge, resources, and dedication of the partners and supporters will strengthen conservation efforts in the UNESCO biosphere region along eastern Georgian Bay. Though the sense of community and collaboration is not easily measured, it can be felt when things are going well. And so far, it feels like things are going well.

To continue this work, donations are gratefully accepted. Georgian Bay Biosphere is a registered Canadian charity and will provide tax receipts for donations over $20.00. Visit gbbr.ca/donate to learn more or email info[at]gbbr.ca.